Moondust will cover you…

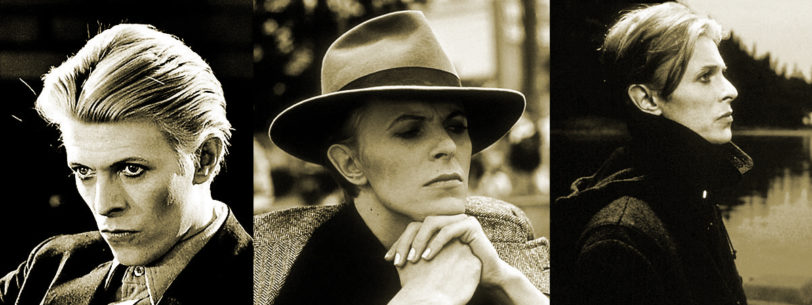

Although he passed back in 2016, it’s still tough to accept that David Bowie is no longer with us. Widely considered one of the most influential musicians of his era, his career is landmarked via invention and experimentation, while also having a key eye on visual presentation.

Much of Bowie’s output demonstrated a willingness to explore musical ideas. If he wasn’t innovating, he was adopting other musical concepts – and often transforming them in the process. Although he never embraced synth-pop directly as a genre, he certainly utilised electronics at significant points in his musical catalogue.

In fact, Bowie was experimenting with electronic instruments such as the Mellotron as far back as 1969’s ‘Space Oddity’, while his work with Brian Eno would result in some of the most innovative electronic compositions of the 1970s.

This month would have marked his 73rd birthday (and also marks the anniversary of his iconic 1977 album Low). To celebrate David Bowie’s extensive musical legacy, we decided to explore some of his compositions that have an electronic element worthy of mention. It’s not a definitive list, but a tourist’s guide to both some obvious songs – as well as some more surprising entries.

![]()

Space Oddity (1969)

Arguably David Bowie’s best-known song, the arrival of ‘Space Oddity’ was timely. Initially inspired by Stanley Kubrick’s film 2001: A Space Odyssey, the release of ‘Space Oddity’ was also timely in that the Apollo 11 moon landing took place just days afterwards, and there was a surge of public interest in space travel and science fiction themes.

Suitably, the song also makes use of space age tech with the use of a Stylophone – its distinctly raw electronic sound dominating much of the composition. It also features a Mellotron (care of Rick Wakeman) to provide a mesmerising spacey strings sound.

‘Space Oddity’ also combined a lot of the ideas that would lay the foundations for Bowie’s work to come: a willingness to experiment with sound and also a desire to weave in a compelling fictional narrative.

Saviour Machine (1970)

Culled from his 1970 album The Man Who Sold The World, Bowie’s sci-fi tale of a computer system designed to end war seems almost custom-built for some electronic dabbling.

While the composition sits on its obvious rock trappings, weaved into the mix are some melodic touches via a Moog 3P modular synth care of concert pianist Ralph Mace, who’d borrowed the synth from none other than George Harrison.

Suffragette City (1972)

As featured on Bowie’s iconic album The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars, ‘Suffragette City’ is another classic number whose driving rhythms are propped up by the relentless piano.

But perhaps one of the song’s most surprising aspects is that the saxophone lines are actually rendered via an ARP 2600 synth. Bowie had originally wanted some big saxophone fills to go up against the guitars and piano, but producer Ken Scott had instead sourced the synth to do the heavy lifting. Working with guitarist Mick Ronson, who was equally at home on keyboards, they fiddled about until they got as close to a sax sound as possible.

Speed Of Life (1977)

You can’t explore Bowie’s electronic output without acknowledging what is probably his key electronic album. Low took on a lot of influence from the likes of Neu!, Tangerine Dream and Kraftwerk, giving the album a brooding European quality. The input of Brian Eno was also essential in how the overall sound of the album shaped up. In particular, Eno’s use of the EMS Synthi AKS (aka the “suitcase synth”) as well as Minimoog and ARP 2600.

‘Speed Of Life’, which kicks the album off, is an instrumental (in fact, Bowie’s first). It also showcases the odd drum sound that Low employed – something that producer Tony Visconti was responsible for by bringing on board the Eventide Harmonizer. This new effects processor could change the pitch (without affecting the duration) of a sound as well as apply delay and feedback effects (describing its use to Bowie, Visconti is claimed to have said that it “fucks with the fabric of time”). For Low’s distinctive drum sound, Visconti used the Harmonizer to sample the drums and, an instant later, echo the sound, but also dropped the drums’ pitch. The result is an odd but dramatic percussion that puzzled fellow producers at the time, but Visconti apparently kept them guessing.

Meanwhile, ‘Speed Of Life’ has an obvious electronic arrangement on top of the live drums that comes courtesy of the ARP and Bowie’s Chamberlin (an early Mellotron-like keyboard).

Warszawa (1977)

The brooding melancholic tones of this Low piece originated with Brian Eno listening to Tony Visconti’s young son repeating a simple sequence of notes on the piano.

That foundation is built up using Eno’s AKS as well as the ARP, Minimoog and Chamberlin (which is responsible for the wind effects). Along with Bowie’s mesmerising vocal, the result is a stark, yet warm slice of electronica.

The track also proved to be a source of inspiration for the pre-Joy Division outfit Warsaw.

“Heroes” (1977)

Another composition culled from Bowie’s Berlin years; ‘”Heroes”‘ became an anthem of sorts for the divided city (the Berlin Wall wouldn’t fall for another thirteen years). Recorded at Hansa Tonstudio in what was then West Berlin, the studio was practically right next to the Berlin Wall.

Robert Fripp’s guitars are distorted through Brian Eno’s AKS, resulting in the other-worldly reedy sound that’s threaded throughout the composition. Even the brass sounds were improvised through the Chamberlin, demonstrating that Bowie was always happy to experiment in the studio to achieve a desired effect.

‘”Heroes”‘ is also a nod to the German school, with the title being an appropriation of ‘Hero’ from the iconic Neu! ’75 album (Neu!’s Michael Rother had actually been Bowie’s original choice to play on the composition). Meanwhile, B-side track ‘V-2 Schneider’ is a tribute to Kraftwerk’s Florian Schneider. Earlier in 1977, Kraftwerk had name-checked Bowie on the title track of Trans-Europe Express, so this could be viewed as Bowie returning the favour.

Sense Of Doubt (1977)

The “Heroes” album features an electronic triptych of sorts, consisting of ‘Neuköln‘, ‘Moss Garden’ and ‘Sense Of Doubt’.

As part of their experimental approach to crafting the music during the Berlin period, Bowie and Eno employed Eno’s Oblique Strategies – a series of cards that represented different commands or suggestions. The idea was to spark innovation and on ‘Sense Of Doubt’ the pair only revealed the cards they drew after the track had been finished. Bowie’s card apparently stated, “Emphasize differences”, while Eno’s read “Try to make everything as similar as possible.”

Although dominated by the weighty piano notes, the track is balanced out with contrasting electronic elements. The end result is a dramatic composition that somehow manages to be both downbeat and optimistic at the same time.

Moss Garden (1977)

Changing direction yet again, this “Heroes” cut is dominated by the use of a koto, a traditional Japanese stringed instrument riding over warm, immersive synth patterns.

As an ambient piece, it’s a wonderland of pastoral tones and creates an oasis of tranquillity for the final third of the album.

Ashes To Ashes (1980)

Bowie entered the 1980s on the back of a strong album in the form of Scary Monsters… and Super Creeps.

That album was heralded by the single ‘Ashes To Ashes’, one of Bowie’s most electronic outings, but not for the reasons you might suspect. Producer Tony Visconti had wanted the distinctive sound of a Wurlitzer, but was unhappy with the hired one the studio received. Instead, the distinctive melody of the song was achieved by feeding the sound of a grand piano through an Eventide Instant Flanger.

Meanwhile, the warm choral elements of the song were actually achieved via a Roland GR500 guitar synthesizer. Enter Chuck Hammer, a skilled guitarist who explored what he called ‘Guitarchitecture’ which combined guitars with electronic treatments. Hammer’s performance was recorded in the back stairwell of the studio, where it reverberated up and down four storeys.

‘Ashes To Ashes’ also features that talents of synth player Andy Clark (who favoured the Minimoog and Yamaha CS-80), a musician who had cut his chops alongside Bill Nelson as part of Be-Bop Deluxe (and their synth-pop offshoot Red Noise). Clark’s contributions can be heard on the song’s outro.

Lyrically, the song also marks an unusual direction by Bowie in which he revisits one of his earlier creations in the form of Major Tom (from 1969’s ‘Space Oddity’), a theme carried over for the promo video. One of the most expensive videos of its time, it’s also notable for featuring some of the people involved in the emerging New Romantic scene at the time (including a young Steve Strange).

Crystal Japan (1980)

This haunting instrumental number sounds more in tune with a slice of Brian Eno ambience, but had apparently been considered as the closing track for the Scary Monsters album (it was actually used for a Japanese TV ad).

Despite the album’s electronic leanings, ‘Crystal Japan’ would have made it an odd fit for the album at the time, cast as a distinctly synthetic composition rather than the dynamic combo of electronics and rock instrumentation that the album employed. It’s an unusual piece, even by Bowie’s standards for instrumental outings, and has a distinctly 1980s flavour to the whole thing.

More unusually, Trent Reznor had somehow absorbed the melody of ‘Crystal Japan’ without realising it and later penned ‘A Warm Place’ for Nine Inch Nails as a result.

Cat People (Putting Out Fire) (1982)

Notable for bringing Bowie together with Giorgio Moroder, this song had sprung from a desire by film director Paul Schrader to have Bowie involved on the soundtrack to his sexually charged film Cat People in some capacity.

Moroder had been charged with composing the film’s soundtrack as a whole, but the combination of both talents produced a surprisingly effective tune. The brooding opening bars were culled from the film’s opening theme (‘The Myth’) and serve as dramatic tension before the track explodes as Bowie emphasises the word “Gasoline!”. Moroder brings in Minimoog and Polymoog on board for a piece that just drips with the brash energy typical of 1980s pop outings. Quentin Tarantino had been so impressed by the song at the time that he later utilised it himself for the soundtrack to his own 2009 brash war film Inglourious Basterds.

A re-recorded version of the song later appeared on Bowie’s 1983 album Let’s Dance.

The Heart’s Filthy Lesson (1995)

Bowie went through something of an industrial phase with his 1995 album 1. Outside (touring the album, he also invited Nine Inch Nails to act as support). It also marked his reunion with Brian Eno and both were keen to return to the exploration of more experimental directions. The result was a concept album of sorts that involved another Bowie-created character called Nathan Adler.

‘The Heart’s Filthy Lesson’ employs a suitably sleazy guitar/electronics direction, often with a disturbing edge to it (the song was also used in the end credits for Michael Fincher’s cult classic Se7en).

Hallo Spaceboy (1996)

Originally penned as another heavy number in line with the other tracks on the 1. Outside album, Bowie later released a remix of the song which features the talents of Pet Shop Boys. As a result, the transformation of the song is extraordinary and marks one of Bowie’s finest 90s moments.

Tasked with expanding the original song’s lyrical content, Neil Tennant and Chris Lowe had suggested reworking lyrics from Bowie’s ‘Space Oddity’. Although Bowie was initially sceptical, both Tennant and Lowe employed Bowie’s own method of cutting up and rearranging the lyrics to present an oddly mesmerising narrative. Bowie, Tennant and Lowe later performed a live version of the remix at the Brit Awards in February 1996.

Soft Cell’s Dave Ball, in collaboration with Ingo Vauk, also turned his considerable remix chops to the PSB take on the song.

Little Wonder (1997)

Bowie’s 1997 album Earthling continued his journey into exploring more electronic directions, but while his previous album 1. Outside had a more industrial bent, Earthling threw more of a nod to drum and bass and dance outfits, including the likes of The Prodigy and Underworld.

There’s certainly a strong Prodigy influence on ‘Little Wonder’, which was Earthling’s second single release.

Much of Earthling utilised instruments that were fed into samplers and electronically treated. It was also the first Bowie album to be recorded entirely digitally.

Pallas Athena (1997)

A track from his Black Tie White Noise album, ‘Pallas Athena’ sees Bowie playing around with drum and bass again.

Intriguingly, Bowie’s record label released special 12” promos of the composition to clubs and DJs that just featured the track’s title (There was concern that Bowie’s name might have a negative impact when presented to club audiences). The approach seemed to work with ‘Pallas Athena’ becoming something of a club hit.

This method of hiding an older act’s name to prevent any misconceptions was also a ruse employed for OMD for one of the singles from their Liberator album in 1993.

I Can’t Give Everything Away (2016)

Bowie’s final album Blackstar was critically acclaimed and ‘I Can’t Give Everything Away’ could be viewed as perhaps the perfect bookend to Bowie’s electronic work. The composition is a lush lounge pop affair with some emphatic percussion and subtle synth flourishes.

A reworked version of the song, known as ‘I Can’t Give Everything Away (Farewell Mix)’, was performed by Nine Inch Nails. Trent Reznor commented that he made the remix as a healing factor to cope with Bowie’s death.

Further listening

BUY NOW

Outside of collecting the various albums that these tracks feature on, a box set capturing Bowie’s crucial 70s/80s output is also available.

A New Career in a New Town (1977–1982) covers the period of Bowie’s career from 1977 to 1982, including his ‘Berlin Trilogy’ albums, over eleven CDs (or thirteen LPs). Exclusive to the box set are a “Heroes” EP, which compiles album and single versions of the song that were recorded in German and French, a new version of Lodger (1979), remixed by co-producer Tony Visconti, and Re:Call 3, a compilation of non-album singles, single versions, and B-sides.

The box set also includes remastered editions of Low, “Heroes”, Lodger, Stage and Scary Monsters… and Super Creeps. The box set did raise some controversy on its release back in 2017, however.

The set comes with a hardcover book with photographs by Anton Corbijn, Helmut Newton, Andrew Kent, Steve Schapiro, Duffy and many others, as well as historical press reviews and technical notes about the albums from producer Tony Visconti.